The Battle of Fisher’s Hill

September 22, 1864

“Our position was naturally strong but our army was too small to man it.”

The Federal victory at the Battle of Fisher’s Hill was a masterpiece of maneuver and surprise. Coming just days after Union Gen. Philip Sheridan’s decisive triumph at Third Winchester, Fisher's Hill opened the Valley to “The Burning,” Sheridan’s systematic campaign to deprive the Confederacy of the agricultural abundance of the Valley.

Following the defeat of his forces at Third Winchester, Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Early withdrew south of Strasburg to Fisher’s Hill. Officers in both armies knew the site well and that if properly defended, it could live up to its reputation as the “Gibraltar of the Valley.” Anchored on the west by Little North Mountain and on the east by the Massanutten, Fisher’s Hill offered Early the opportunity to defend the Valley at its narrowest point.

Confederates had held Fisher’s Hill in August and deterred Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah from assaulting the position. Early hoped for the same success in late September. However, circumstances had changed. In August, Early had the numerical capabilities to defend the four mile stretch from the Massanutten to Little North Mountain, but in late September he did not. Nearly 4,000 casualties, the deployment of Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry to the Luray Valley, and the redeployment of elements from Gen. John C. Breckinridge’s command to the Department of Southwest Virginia diminished Early’s strength and limited his ability to make good defensive use of Fisher’s Hill.

On the afternoon of September 20, Union Gen. Philip Sheridan and his staff stared at the lofty heights of Fisher’s Hill. After conferring with his corps commanders, Sheridan ruled out a direct frontal assault and contemplated the advice of VIII Corps commander Gen. George Crook to swing around to the west and strike Early’s left flank. Sheridan approved the plan.Crook needed to maintain secrecy throughout the entire flank march, so much of it occurred under the cover of darkness or amid the fall foliage in order to avoid detection from the Confederate signal station atop Signal Knob on the Massanutten. While Crook marched his command, the Union VI and XIX Corps massed north of Fisher’s Hill. On September 21 a portion of the VI Corps seized Flint Hill – a piece of high ground north of Tumbling Run essential to Sheridan’s plans. Meanwhile, to distract the Confederates, the rest of the Federals demonstrated and probed Early’s line throughout September 22, even though some “could not discern a living creature over there.”

“The squirrels and stray pigs over there must have wondered what we had against them.”

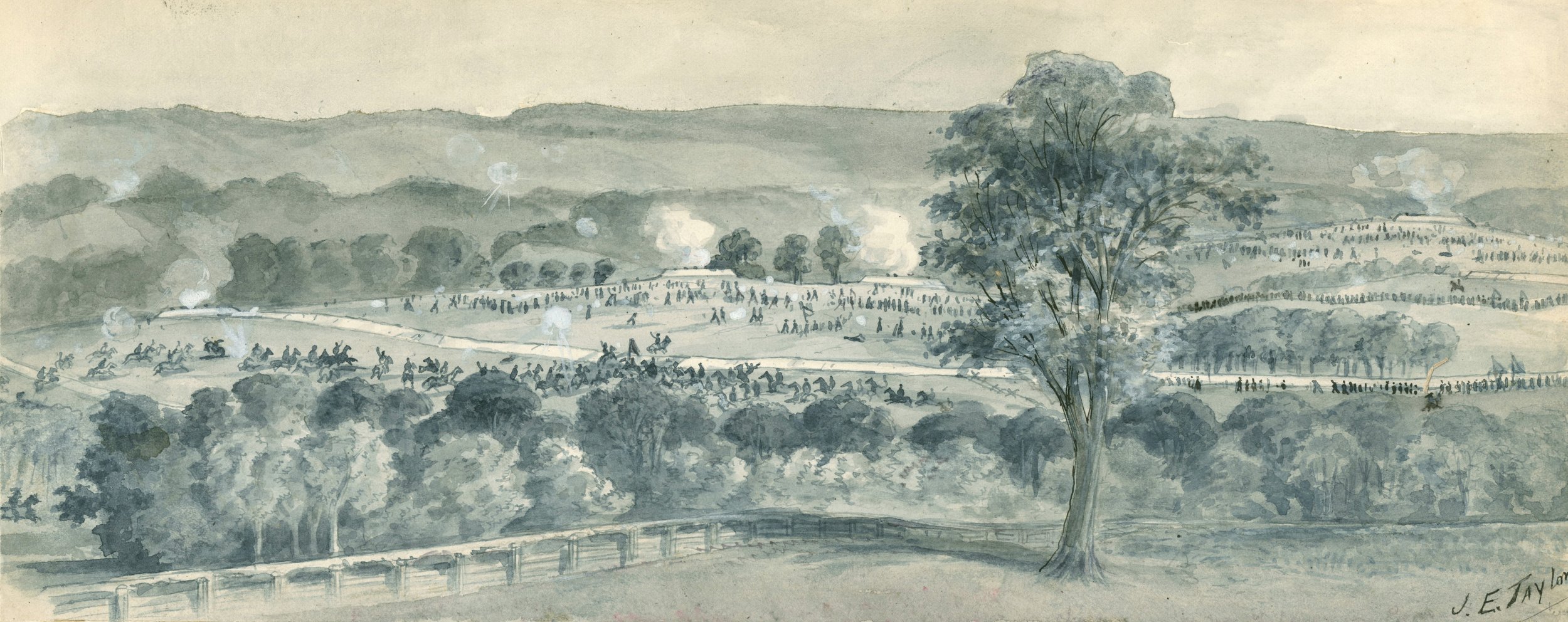

By 2:00 p.m. on September 22 Crook’s men began to climb the slopes of Little North Mountain. Approximately two hours later Crook’s two divisions formed lines of battle and surged “like a western cyclone” toward the Confederate left. Confederate cavalry under Gen. Lunsford Lomax failed to provide any advance warning or slow the advance. Soon Crook’s men rushed headlong in a confused, but determined mass into the main line of Confederate infantry commanded by Gen. Stephen D. Ramseur. Although Confederates tried desperately to stem the tide, the pressure from the flank attack and subsequent frontal assaults of the VI and XIX Corps forced Early to withdraw. Sheridan’s troops pursued Early’s battered command through the night to Woodstock.

“A cavalryman came down our line telling the men they were flanked…I have often regretted I did not shoot him.”

George Crook’s men attacking down the slopes of Fisher’s Hill

Following the battle, Early withdrew south, seeking the safety of the western slopes of the Blue Ridge. Federal forces then embarked on “The Burning,” a two-week campaign of destruction to neutralize the Shenandoah Valley’s agricultural base, this “breadbasket of the Confederacy.” After additional Union victories at Tom’s Brook (October 9) and Cedar Creek (October 19), the Confederacy had lost control of the Valley. Six months later, the war in Virginia ended in the small town of Appomattox.