The Third Battle of Winchester

by Brandon H. Beck

The Third Battle of Winchester on September 19, 1864, the largest and bloodiest Civil War battle in the Shenandoah Valley, had great strategic significance both in the Valley and in the wider war. It proved to be the climax of Lt. Gen Jubal Early’s Valley Campaign and the beginning of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s decisive one-month campaign that finally wrested the Valley from Confederate control.

Robert E. Lee

Gen. Robert E. Lee, commanding the Army of Northern Virginia, intended for Early’s campaign to repeat the strategic success of Stonewall Jackson’s fabled 1862 Valley Campaign. Surveying the military situation across the Old Dominion after his defeat of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Potomac on June 12-13, Lee saw the necessity of relieving Union pressure on Lynchburg, west of the Blue Ridge. The city served as the conduit through which the Valley’s summer and autumn harvest would reach Lee’s hungry soldiers. To that end, Lee sent his battle-hardened, but much reduced, Second Corps under Early to Lynchburg. Early succeeded brilliantly, saving the city and advancing northward down the Valley. He passed through Winchester, crossed the Potomac, and threatened Washington (July 11-12). He then fell back, winning victories at Cool Spring (July 16) and Kernstown (July 24).

Jubal A. Early

Early’s successes compelled Grant to send forces west, toward Washington and the Valley. However, the reaction in Washington to the stinging defeat at Kernstown proved decisive. President Lincoln created a unified Middle Military Division (more popularly known as the Army of the Shenandoah), placing it under Sheridan’s command. He was to command three infantry corps (VI, VIII, and XIX) and three divisions of cavalry.

Against a force of that size and power Early could not afford error or misstep. In 1862 Jackson made no critical mistakes and used reinforcements to seal the success of his campaign in the First Battle of Winchester (May 25, 1862). In 1864, despite how careful Early might have been, there were no reinforcements. Instead, on September 14 a division of infantry and two battalions of artillery left the Valley bound for Richmond and Petersburg.

Rebecca Wright and Thomas Laws

The departure of this Confederate force, made known to Sheridan by Winchester Unionist Rebecca Wright and African-American Thomas Laws, left Early with just over 15,000 men. Sheridan’s command, then near Harper’s Ferry, numbered over 40,000. Early then unwisely divided his force, further compounding his weakness. He sent three infantry divisions under Generals Robert Rodes, John Gordon, and Gabriel Wharton toward the main line of the Baltimore & Ohio R.R. at Martinsburg. That left only Gen. Stephen Ramseur’s division at Winchester, east of town guarding the Berryville Pike (today’s Rt. 7). Union cavalry reported Early’s maneuver to Sheridan, impelling him to strike Winchester on September 19.

Sheridan planned to cross Opequon Creek east of Winchester and defeat the Confederates as they attempted to concentrate. Two cavalry divisions under Gen. Wesley Merritt and Gen. William Averell intended to cross at fords north of the Berryville Pike crossing. The third cavalry division under Gen.

James Wilson would lead the infantry across at Spout Spring’s Ford. These heavy columns would press on through the defile locally known as the Berryville Canyon, hoping to crush Ramseur’s small division before any other Confederate divisions could reach him.

Early, however, realized his mistake on September 18, and rushed to collect his force east of Winchester on a line running north from Ramseur’s position to just beyond Red Bud Run. Rodes’ division was on Ramseur’s immediate left; Gordon’s division extended from Rodes’ left toward Red Bud. Confederate units farther north as far as Stephenson’s Depot, were under the command of Early’s second-in-command, Gen. John C. Breckinridge.

Philip H. Sheridan

Sheridan’s plan miscarried. Ramseur’s division resisted stubbornly in the Berryville Canyon, while Wilson’s cavalry, Gen. Horatio Wright’s VI Corps, and Gen. William H. Emory’s XIX Corps became embroiled in a “traffic jam” of their own making. Sheridan’s advance was not the lightning-like thrust he had envisioned. Instead, his tired and frustrated columns emerged from the Berryville Canyon at about 11 a.m. already demoralized by numerous casualties. Upon seeing a Confederate battle line formed in their front east of Winchester, officers and men knew they were in for a hard day. A soldier in the 121st New York remarked that among those Confederates were “the Louisianans of Rappahannock Station…the Alabamians of Salem Church, the Virginians and Georgians of the Wilderness, and [Gen. Cullen A] Battle’s men of Spotsylvania.” More Confederates were on the way.

At 11:40 a.m. Early ordered Gen. Breckinridge, in command of Confederate forces at Stephenson’s Depot, to join the main force at once. Though outnumbered, Early’s veterans were ready to give battle.

Once formed, the troops of the VI and XIX Corps did not falter. They began a general advance on the Rebels just before noon. But as they advanced large gaps appeared between their formations, particularly between the left of the VI Corps and the right of the XIX Corps. The former guided on the Berryville Pike, which turned away to skirt the Dinkle property, while the latter moved toward the very heavy and accurate fire coming in from their direct front. One veteran recorded: “A great yawning gap had opened up in Sheridan’s front and the Confederate reaction was almost instinctive. They [Rodes and Gordon] struck with a power born of desperation and opportunity.”

The Confederate counterattacks splintered the Union front. A Union Captain, John DeForest serving in the XIX Corps, wrote that “my adjutant called me to look to the left…behold! [Gen. James] Rickett’s division was gone…in place of it was a sea of prisoners…the Pike was crowded with fugitives.” Capt. Robert Packs, of Battle’s brigade, saw Gen. Early as the Confederates pressed forward. “I lifted my hat to the old man as we ran forward,” Packs wrote, “we raised our well known Rebel yell and continued on.”

Two generals were killed in the advance—Confederate Gen. Rodes and Union Gen. David A. Russell. When Rodes fell, Early made a fateful decision ordering Gen. Bryan Grimes, Rodes’ successor, to halt the Confederate attack. “Wait for Breckinridge,” Early ordered. On the Union side, Russell’s successor, Col. Emory Upton, moved his three brigades into the gap momentarily halting the Rebels. Early’s decision may have been the right one, but it was a harbinger of his more famous halt order at Cedar Creek one month later.

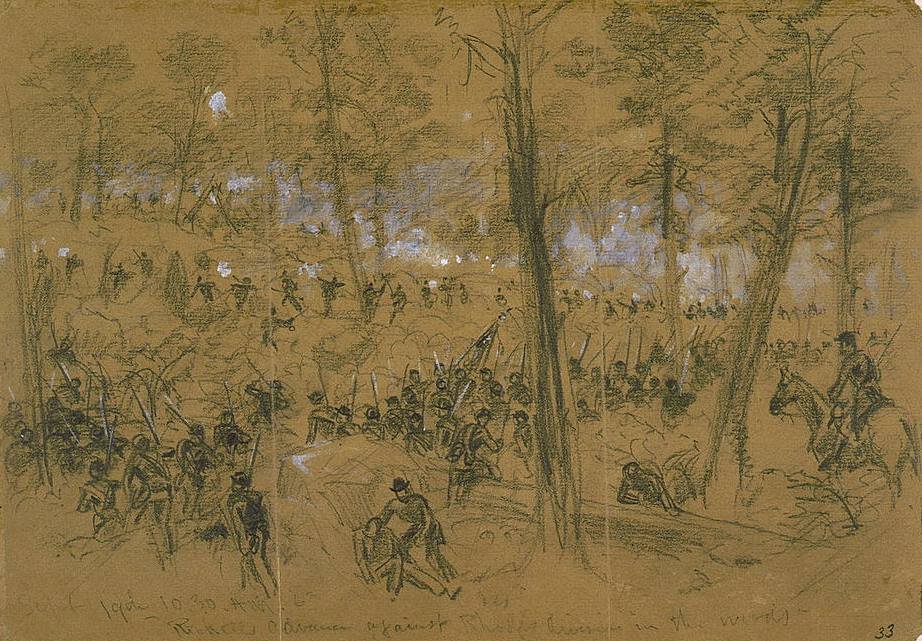

Rickett’s Division attacking into West Woods

As the Confederates fell back to their original positions, the battle settled into a static, but rather deadly standoff. Both armies held their ground and exchanged crushing, accurate volleys. Capt. DeForest wrote: “The men on both sides were nearly all old soldiers who knew their deadly business…our adversaries were no doubt good shots, and besides, they fired more continuously than we did.”

The deadly exchanges continued until mid-afternoon. During this time Early could easily have broken off the battle and withdrawn up the Valley Pike. Not only was he too combative to do so, but he must have also been encouraged by the excellent performance of his artillery, which provided strong support for the infantry throughout the day.

Sheridan, too, was determined to continue. Unlike Early, he had a significant number of men not yet engaged; two divisions of Gen. George Crook’s VIII Corps, and two divisions of cavalry now concentrating at Stephenson’s Depot. Crook’s divisions (Col. Joseph Thoburn and Col. Isaac Duval) had by 3 p.m. cleared the Berryville Canyon and were within reach. They must be sent in—the question was where?

Sheridan chose to move by his own right flank, against Early’s left. Turning the Confederate left would drive Early across the Union front. Either Sheridan or Crook—it became an enormous dispute between the two that ruined their friendship—decided to advance the two divisions along both banks of Red Bud Run and hit Early’s left flank anchored at Hackwood. Thoburn advanced on the near bank; Duval would cross, move parallel with Thoburn, and then re-cross at the point of attack.

Duval was struck down in the attack putting Col. Rutherford B. Hayes of the 23rd Ohio in charge of leading the division across. Visitors to the site today will marvel at the fact that the crossing of this steepbanked, slow moving swampy stream was accomplished at all. Furthermore, Gordon’s brigade vigilantly held the Confederate left and had been slightly reinforced with Early’s remaining reserves. Hayes got his men across under heavy fire, but could advance no farther than Hackwood. There, according to the 23rd Ohio’s Russell Hastings, “All about the bridge, the banks of the Creek, and up the lawn to the buildings the dead of the 23rd were literally lying in heaps.”

Thoburn’s assault, delivered simultaneously with Duval’s, pushed Gordon’s front back. It also triggered several seemingly spontaneous attacks at various places along the Union front including the notable bayonet charge of the 8th Vermont. In the end the Confederates gave ground, but maintained their flank and their cohesion while exacting a high price in Union casualties as they contracted their line of battle. By about 5 p.m. the Confederate line had taken on the shape of an inverted “L,” with the short arm across the Martinsburg Pike, facing Stephenson’s Depot, four miles to the north. In the right angle of the “L” sat Fort Collier, and earthen fort built in 1861, a few yards east of the pike.

The VIII Corps could do no more as Early remained unwilling to break off the battle. A brief lull in the fighting settled over the bloody fields. A Confederate artillerist in Fort Collier, Milton Humphreys, wrote that “everything seemed deadly quiet.” The outcome of the battle was still undetermined.

Around 5 p.m. Sheridan ordered in his last uncommitted forces—the cavalry divisions of Merritt and Averell. They had crossed the Opequon at first light and had been skirmishing and concentrating near Stephenson’s Depot since early morning. Now six brigades strong, this enormous force set itself in motion on either side of the pike, a “thunderbolt” aimed at the Confederate left. The troopers moved slowly at first. Col. William Powell’s and Col. James Schoonmaker’s brigades advanced west of the pike, Gen. George Custer’s command most nearly astride it, and Col. Thomas Devin’s and Col. Charles Russell Lowell’s brigades moved east of the pike. Between them and the scratch force in Fort Collier were only a few cavalry units and the three small infantry regiments of Col. George S. Patton’s brigade. The cavalry rode over and through them, smashing the hollow squares the men vainly formed. Patton was mortally wounded in an attempt to rally his disorganized command in one of Winchester’s narrow streets—he died on September 25. The blue clad horsemen swept on, faster now, and crushed the Confederate infantry in Fort Collier. Despite valiant attempts of artillerists from Lt. Col. J. Floyd King’s battalion to fire the two cannon in Fort Collier, the blue tide was irresistible, sweeping around and then into Fort Collier’s interior.

The Union cavalry charge that broke the Confederate lines at Third Winchester – “Sheridan’s Final Charge at Winchester” by Thure de Thulstrup (Library of Congress)

The fall of Fort Collier to fast moving cavalry was too much for tired, outnumbered men to endure. The great cavalry charge unhinged the Confederate line of battle. Sheridan saw what was happening, and was suddenly everywhere urging his men forward. The rout had begun.

Early, with admirable presence of mind, ordered Col. Thomas Munford’s cavalry to hold Star Fort—to the west of Fort Collier—against Schoonmaker’s brigade. Munford succeeded and brought up some artillery as well, which slowed the pursuit. Infantry from Gen. Ramseur’s division and Gen. Grime’s brigade made a stand in the Mt. Hebron Cemetery and Sheridan did not push his pursuit past Winchester’s southern edge.

Casualties on both sides were very high. Early reported 227 killed, 1,567 wounded, and 1,818 missing or captured. Sheridan too paid a high price for success—697 killed, 3,983 wounded, and 338 missing or captured. Sheridan, however, had more men and could afford the loss. The high numbers of wounded on both sides prompted Sheridan to establish the Civil War’s largest tent hospital at Shawnee Springs in Winchester—traces of which still exist today.

Following the defeat at Winchester, Early withdrew south to Fisher’s Hill, where his men entrenched in the hopes of blocking Sheridan’s advance up the Valley. Third Winchester had changed the momentum of the war in the Valley. “Have just heard of your great victory,” President Lincoln wired Sheridan the day after the battle, “God bless you all, officers and men. Strongly inclined to come up and see you.” Although victorious at Winchester Sheridan knew there was much work still to be done as his adversary “Old Jube” was not yet ready to give the Valley entirely to the Union Army of the Shenandoah.

About the Author:

Brandon H. Beck was the Hugh D. and Virginia McCormick Professor of Civil War History at Shenandoah University for more than twenty years and is currently director emeritus of the University’s McCormick Civil War Institute. He has authored or edited eight books including The Third Battle of Winchester and The Three Battles of Winchester: A History and Guided Tour.

This article is included in the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation’s booklet, “Give the enemy no rest!”: Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Campaign. To purchase copy from our online store, click the link here.