The Cavalry Engagement at Tom’s Brook

by William J. Miller

Gen. Philip Sheridan’s torch-wielding Federal cavalrymen ignited more than barns, mills, and crop fields in “The Burning” of the Shenandoah in the first week of October 1864. With every pillar of smoke they sent skyward, the Northern horsemen inflamed Confederate soldiers to hatred and a hunger for vengeance. The ruthless tactics of Sheridan’s cavalry provoked an outraged response from the increasingly weak and frustrated Southern fighting men in the Valley. Perturbed most of all were Confederate cavalrymen responsible for keeping their Northern counterparts in check. The Southern cavalry was weak, poorly mounted, and badly aggravated by their impotence. The rising passions set the stage for a climactic confrontation between the Federal burners and the proud Confederate horsemen who felt powerless to prevent the desolation that was settling over their homeland.

Thomas L. Rosser

Gen. Jubal Early’s two tiny Confederate cavalry divisions were ill-equipped and badly mounted in that first week of October. Maj. Gen. Lunsford Lindsay Lomax, a former staff officer with little experience in the cavalry, led one of these “divisions,” which consisted of just 800 men. Early’s other cavalry division was larger, but still small and troubled and under a new commander, Brig. Gen. Thomas L. Rosser who had never led more than a brigade. Blunt and brave to a fault, the twenty-eight-year-old Rosser had served since the war’s outset and had sustained no fewer than four wounds. He owned an unquestioned reputation for aggressiveness and courage, but command of a division called for discretion as well as gallantry, and the oft-wounded and sometimes reckless Rosser could have trouble balancing the two virtues.

George A. Custer

In contrast, the Union cavalry in the Valley was as strong as it had ever been. Sheridan’s cavalry chief, Brig. Gen. Alfred Torbert, commanded about 9,000 well-supplied and well-mounted cavalrymen. Youthful and experienced leaders, including Brig. Gen. George A. Custer and Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt, infused the Northern units with vigor and aggressiveness, which made Sheridan’s mounted arm a formidable force.

The Valley Turnpike

The emotional impact of “The Burning” on the Confederates cannot be overestimated. Rosser understood that many of the defiled homesteads belonged to men in his command, and it was clear to him that they were moved to hatred. A Confederate colonel confessed that, when Federal horsemen fell into their hands, many cavalrymen native to the Valley “took no prisoners.” Another officer declared that his men were, “blinded with rage at the sight of their ruined homes,” and drove onward, “impelled by a sense of personal injury.” Despite their small numbers and the wretched condition of their horses, the Southern troopers pursued and harassed the Federals northward through the Valley. Sheridan, also a man of strong passions, found this hounding pursuit galling. On the night of October 8, the army commander angrily ordered Torbert to send out his divisions the next morning and either whip the Confederate cavalry “or get whipped himself.”

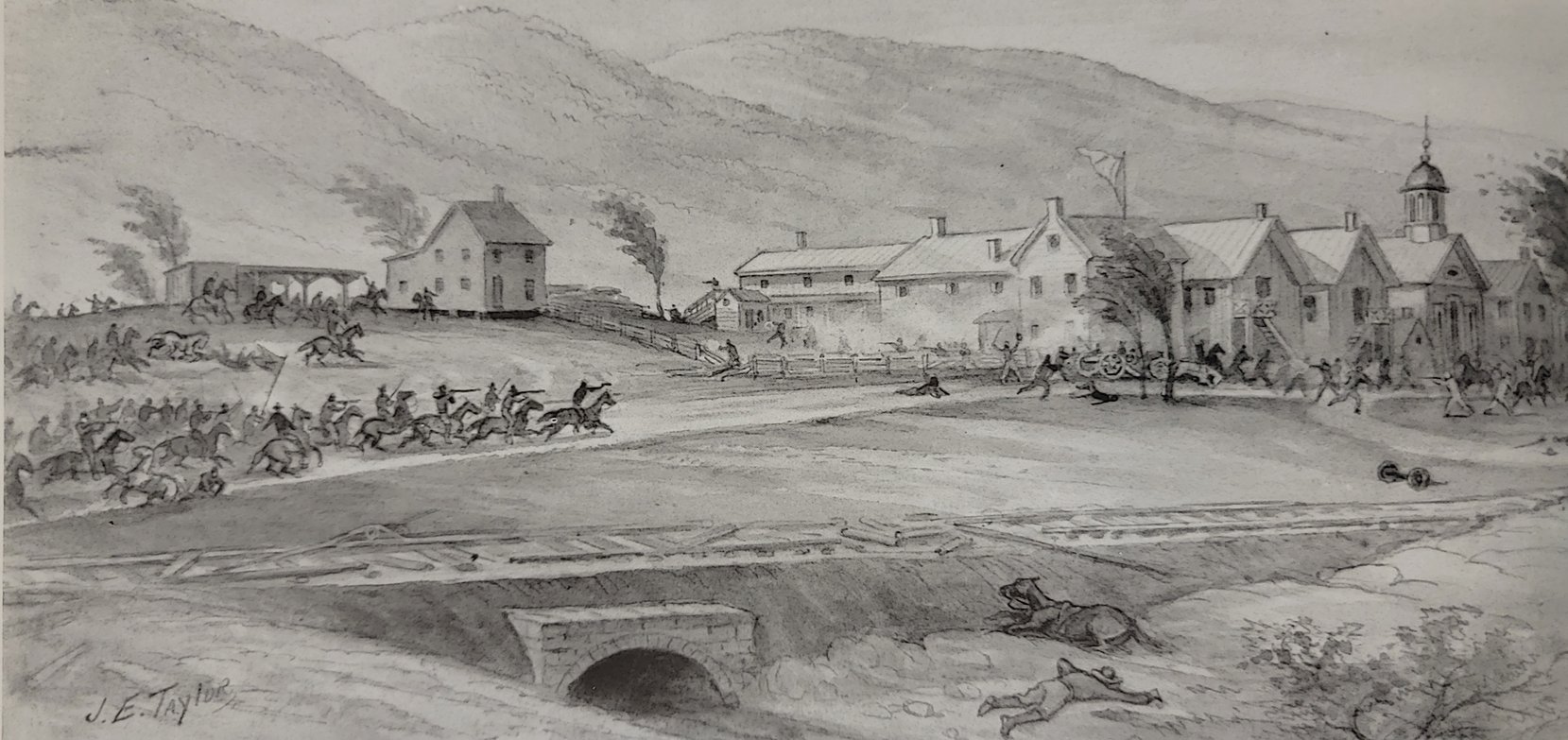

At dawn on October 9, Custer and Merritt had their men in the saddle moving southward from their camps north and west of the hamlet of Tom’s Brook, which took its name from a nearby stream. Custer deployed his men astride the Back Road. Merritt’s men moved through the sleeping village on the Valley Turnpike. The two commanders had a rough plan to work in concert as the fight progressed. Merritt’s division was to move southward through the village and on to the high ridges south of the brook. Having secured the high ground, Merritt would turn westward toward the Back Road and concentrate on the flank of any enemy force and, with Custer, rout it. In effect, however, Merritt and Custer, and their Confederate counterparts, Lomax and Rosser, would fight independent actions, making the Battle of Tom’s Brook essentially two engagements fought less than two miles apart.

Custer deployed in long lines extending on both sides of the Back Road. Rank after rank of Northern horsemen swept southward toward Rosser’s position on Spiker’s Hill, just south of where Tom’s Brook crossed the road. Wind and stray snow flurries chilled the gathering soldiers, but more chilling for the Confederates was the view of the meadows north of the creek. One Southerner peering through the tree cover found that “every opening disclosed moving masses of bluecoats. . .covering the hill slopes and blocking the roads with apparently countless squadrons.” Confederate Col. Thomas Munford saw the obvious and stated it to Rosser as they sat surveying the scene. With fewer than 2,000 men at their disposal, Munford declared, they could not expect to defeat Custer’s entire division. The weak Confederate position lacked the men to cover the flanks, both of which were exposed. According to Munford, Rosser replied in “a vaunting manner” that he would drive the Federals from the field by 10 o’clock.

A mile-and-a-half to the east, Lomax held his 800 men with a battery of artillery on the high ground south of Jordon’s Run, deployed on both sides of the Valley Pike. Bradley T. Johnson, a brigadier general of long experience, commanded the Confederates east of the turnpike while Lt. Col. William P. Thompson, led Lomax’s other, larger, brigade, known as “Jackson’s Brigade,” west of the road. The six guns of the Baltimore Light Artillery stood in the middle of the line. Lomax faced disaster as soon as the first Federal regiment came into view that morning. So few were his men and so woeful was the condition of their horses and weapons that Lomax could not reasonably expect to fend off a determined Federal attack, and he unquestionably knew as much. Many of his troopers had no weapons at all, and by Lomax’s own admission he could not hope to resist a mounted charge because his men had no arms with which to fight on horseback, “not a saber or pistol being in the command.”

Merritt divided his command, pushing Col. James Lowell’s brigade against Lomax’s front while shifting Col. Thomas C. Devin’s brigade around the Confederate left flank. Despite the advantage of the high, steep ridge, Lomax’s position was exceptionally vulnerable. The Confederate commander had men enough to resist on a narrow front, but did not have the numbers to cover the vulnerable flanks. Devin met slight resistance as he maneuvered his men to the west of the pike, and he soon gained the ridge on the Confederate left. At that instant, Lomax’s position became untenable, and the Confederate commander had no choice but to withdraw—and quickly.

On the Back Road, Rosser had deployed his troopers in a shallow arc across the northern face of Spiker’s Hill. A Federal battery opened fire at long range then moved forward to a better position as Custer’s troopers advanced. The Confederate guns on Spiker’s Hill replied but had little effect against the superior Federal artillery. Beneath the umbrella of shot and shell, the cavalrymen, mounted and on foot, went to work in the creek bottom.

The opponents searched and probed, looking for openings. The fighting grew furious at times as charge and countercharge kept the contest in balance. Col. William H. F. Payne’s brigade made three gallant countercharges to blunt Federal forays. Despite harassment from their Union counterparts, the Confederate gunners on the hill maintained an accurate, plunging fire on the blue-coated cavalrymen trying to force a crossing of the brook. After less than an hour of combat, Custer had suffered few casualties but had come to realize he would make no headway with frontal attacks. He had an abundance of men at his disposal, and, through the increasing smoke, he considered how he might use them to best advantage.

Knowing that he outnumbered Rosser, Custer extended his line westward. His plan was essentially identical to Merritt’s: distract the enemy with frontal attacks while sending a strong force around the left flank. If Rosser discovered this extension, he would be forced to extend his own line to protect more ground with his small force and thus weaken his line everywhere. If Rosser did not discover the extension to the west, his left flank would be caught by surprise, turned, and the entire Confederate position rendered untenable.

Custer sent two regiments, under the command of Lt. Col. William H. Benjamin, around Rosser’s left. Soon, he saw Federal cavalry arriving on his own left flank (opposite the Confederate right). Custer recognized the uniforms of Col. James Kidd’s Michigan brigade, part of Merritt’s division. Just ten days earlier, this had been Custer’s brigade. He and the Michiganders had risen to fame together. Custer recognized the arrival of Kidd on the Confederate right as fortuitous, for Benjamin’s flanking column would soon attack the Confederate left. Hoping to hit Rosser’s outnumbered men from three sides at once, Custer launched the final frontal push upon Spiker’s Hill from his center. He rode in among the men of the 5th New York and the 18th Pennsylvania and personally led a charge up the hill.

It was too much for Rosser’s brave but few troopers. As the Federals struck, seemingly from every direction, Capt. Mottrom D. Ball of the 11th Virginia turned to see “the whole country to my left rear covered with the flying regiments of other brigades, the enemy pressing them close.” The Confederate defense dissolved in sudden chaos as hundreds of veteran Confederate troops fled in panic.

Most of Rosser’s men fled southwestward on the Back Road, but some took a side road just in the rear of Spiker’s Hill and fled almost due southward, through the village of Saumsville, and toward Woodstock. The Federals pressed everywhere. On the Back Road, Custer’s men harassed Rosser’s men all the way to Columbia Furnace, nineteen miles from Spiker’s Hill.

On the Valley Pike matters were little different After the short engagement on Jordon Run, an engagement more maneuver than combat, the Confederates retreated briskly. The valiant Lomax aggressively organized rear-guard stands on advantageous ridges along the Valley Pike. “General Lomax was everywhere on the field,” recalled one soldier, “animating and cheering his men in the hour of defeat. . . .” In the swirling fights along the Pike, the Federal pursuers succeeded in capturing many Confederates, including Lomax, but they could not hold him. The division commander escaped by knocking one of his captors to the ground and joining in a Federal charge upon his own men. He later joked that he was the bravest among the Yankees “for he charged right into the rebels.”

General Custer doffing his hat in a knightly gesture to his old West Point classmate Gen. Thomas Rosser (Alfred Waud - Library of Congress)

Southward the Confederates fled, through Edinburg and Hawkinstown and Mt. Jackson. At last, the pursuers crested a ridge just south of Mt. Jackson and halted. They stood more than twenty-two miles from the banks of Tom’s Brook, where the long chase had begun. The Federals watched as the exhausted Confederates on their faltering horses passed over the North Fork of the Shenandoah River and into the protecting embrace of Southern infantry support.

A paucity of records makes it impossible to determine the casualties and captures on October 9, 1864. Rosser, understandably reluctant to chronicle the extent of the disaster, made no report. Lomax admitted his material losses, but did not suggest a figure for his losses in men or animals. Merritt reported the capture of forty-three wagons full of ordnance, arms and stores, five pieces of artillery with limbers, three ambulances, many caissons, forges, mules, horses, and more than four dozen prisoners. Custer had taken six pieces of artillery, the headquarters’ wagons of Rosser and Munford, the division’s ordnance, ambulance and wagon trains, and “a large number of prisoners.” Sheridan informally estimated the number of Confederate prisoners at about 330. Torbert set total Federal losses at fewer than sixty men killed or wounded.

Tom’s Brook was a clear victory with real consequences. The Federals had effectively, if not literally, destroyed the Southern cavalry in the Valley. Mounted Confederates never again played an important role in Jubal Early’s operations. The result was all the more regrettable for the Southerners because the fight was completely unnecessary. The outraged Southern troopers had given full rein to their passions as they blindly sought vengeance against the Yankee farm burners. Their commanders, Lomax and Rosser, had little to gain by forcing a confrontation with more than twice their number of Federals, but they had obstinately stood in the face of insuperable odds. Passions and hubris had clouded judgment on the south bank of Tom’s Brook, and defeat and disaster were the predictable results.

About the Author:

William J. Miller has written extensively about the Civil War in Virginia, including Decision at Tom’s Brook: George Custer, Thomas Rosser and the Joy of the Fight, Mapping for Stonewall: the Civil War Service of Jed Hotchkiss, and Great Maps of the Civil War. He is a former editor of Civil War Magazine, has published more than 100 articles on the conflict, and frequently leads battlefield tours (see Tour Shenandoah Battlefields website here.)