The Battle of Tom’s Brook

October 9, 1864

“Whip the rebel cavalry or get whipped yourself.”

Gen. George A. Custer doffing his hat in a knightly gesture to his old West Point classmate, Confederate Gen. Thomas L. Rosser

The all-cavalry Battle of Tom’s Brook was a decisive Union triumph that reflected the growing dominance of Union horse soldiers in the Shenandoah Valley. The outnumbered Confederate cavalry, eager for revenge on Federal troops carrying out the destruction of The Burning, had advanced far beyond their infantry support, leaving them vulnerable when the Federals turned to attack on October 9, 1864. The resulting Union rout of the southerners became known as “The Woodstock Races.”

As Union cavalry carried out “The Burning” in early October 1864, Confederate cavalry followed close behind, ordered by Confederate commander Gen. Jubal A. Early “to pursue the enemy, to harass him, and to ascertain his purposes.” Among the cavalry were reinforcements sent from Petersburg, the “Laurel Brigade” under Gen. Thomas Rosser, called by some the “Savior of the Valley.” Many members of his brigade were Valley natives, and the Federal destruction left them “blinded with rage at the sight of their ruined homes.” Eager for vengeance, they hammered relentlessly at the Federals on October 6-8, forcing them back “in one continuous running fight” – and, as one southern officer remembered, “in many cases [taking] no prisoners.”

Union commander Gen. Philip H. Sheridan was infuriated by the attacks. On the night of October 8, he summoned his cavalry commander, Gen. Alfred Torbert, and ordered him to “whip the rebel cavalry or get whipped” – and to “finish this ‘Savior of the Valley’.”

Meanwhile, the aggressiveness of the Confederate cavalry had left the southern horsemen vulnerable. Not only were they heavily outnumbered, but they had advanced dangerously ahead of their infantry support, which was 20 miles south – almost a full day’s march away.

The Federal attack on October 9 took place on two main fronts. On the east, along the Valley Pike, Union Gen. Wesley Merritt advanced against Confederate Gen. Lunsford Lomax. Two miles to the west, along the Back Road, Rosser faced an old friend, Union Gen. George A. Custer. The two had been classmates at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point before the war.

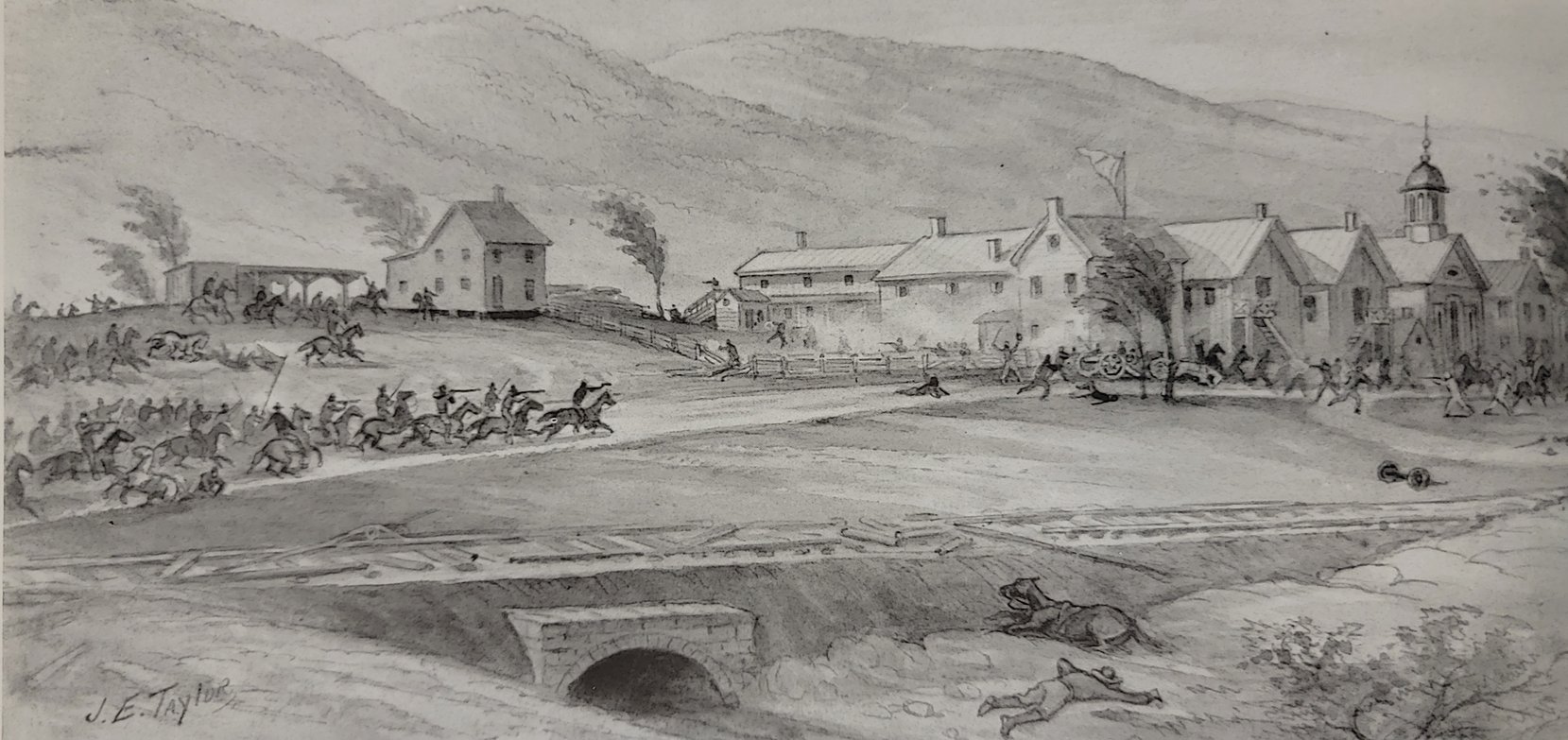

As Custer advanced on the Back Road, Rosser dismounted most of his troopers behind Tom’s Brook, at the base of Coffman’s Hill, behind stone fences and makeshift fieldworks, with six guns on the crest of the hill behind him. Spotting Rosser, Custer rode out in front of the line, removed his hat, and bowed, a theatrical gesture that artist James Taylor said “was like the action of a Knight in the Lists!”

A more daunting site to the defenders was the number of Federal horsemen “covering the hill slopes and blocking the roads with apparently countless squadrons.” The Confederates held stubbornly for several hours against the initial attacks, but then Custer ordered a flanking maneuver and a renewed frontal assault. Combined with an attack on Rosser’s other flank by the brigade of Col. James A. Kidd (part of Merritt’s division), which advanced into the gap between the Rosser and Lomax, this assault collapsed the outmanned rebel line.

At the same time, a similar story played out along the Valley Pike, as Merritt’s forces flanked, overwhelmed, and drove back Lomax’s woefully outnumbered Confederates. The rout became total. At one point, Lomax was captured by the Federals, but escaped after breaking away and joining in a Union charge on his own men. The Federals pursued the Confederates southward for almost 20 miles to Mt. Jackson – the famed “Woodstock Races.”

The ease and completeness of the victory led many Federals to believe that Early’s forces were “permanently broken.” Just how wrong they were would become clear 10 days later at The Battle of Cedar Creek.